Lesbians you should know about: Mary Renault

Beloved by a generation of gay men for her queer novels, Mary Renault was a complex character who defied the conservativism of the 50s and 60s.

Historical accounts about the lives of LGBTQIA+ people in the past are few and far between and stumbling across a notable queer person one didn’t know about is always a joy.

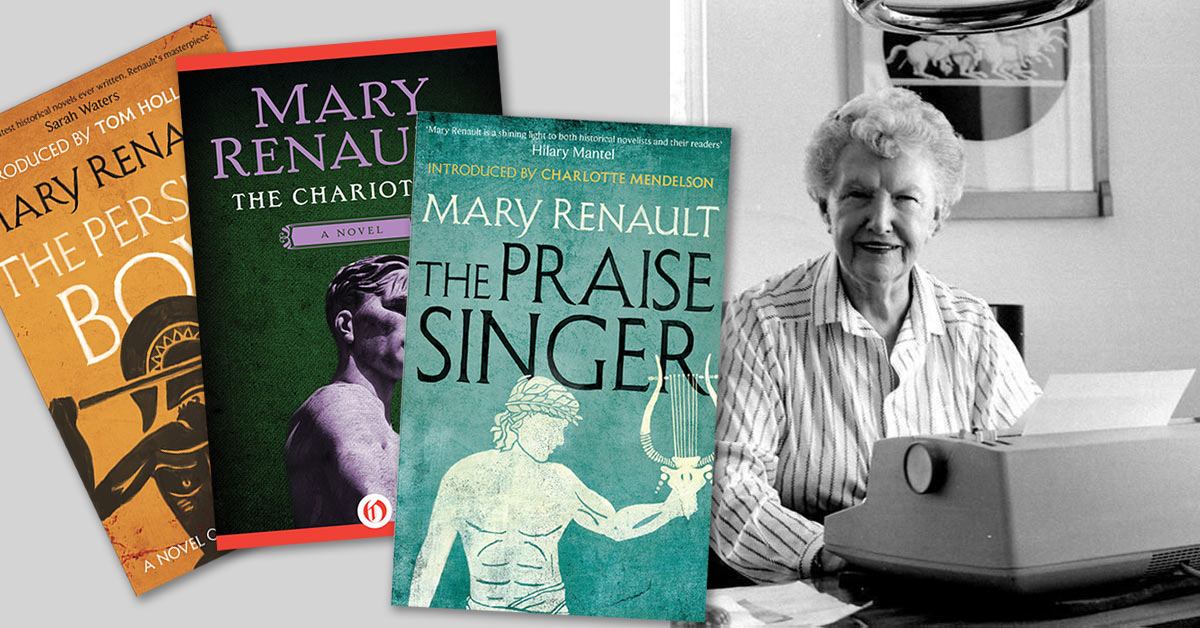

One such lesser-known lesbian (at least to the lesbian writing this article) is Mary Renault, a writer of historical queer fiction from the 1930s to the 1980s who also spent a significant part of her life in South Africa.

Born Eileen Mary Challans, Renault trained as a nurse, following her father’s refusal to support her writing career. While qualifying at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford, England, Renault met fellow nurse Julie Mullard, the woman she would end up spending the rest of her life with.

Renault’s first novel, Purposes of Love (1939), was written while still working as a nurse, and she went on to write three more books before being awarded the MGM prize for Return to Night (1947), which enabled her to write full-time. It was also during this period that Renault and Mullard emigrated to Durban in South Africa, where they would live until shortly before Renault’s death in 1983.

While Renault’s first novels all featured contemporary settings, it was her historical fiction, and especially her gay historical fiction, that drew attention and cemented her into the literary scene. Surprisingly, Renault only wrote one lesbian novel — The Friendly Young Ladies (1944). This book, which centres on the love affair between a writer and a nurse, is thought to be based on the relationship between Renault and Mullard.

Starting with The Charioteer, which was published in 1953, Renault’s fondness of ancient Greece started to take a more prominent role in her writing. This book told the story of two young gay servicemen who use classical Greek ideals to make sense of their masculinity and their relationship.

One of the first so-called “gay novels”, Renault’s juxtaposition of the tolerance of ancient Greece and the more conservative attitudes that contemporary Britain had about homosexual relationships made her a much-loved author among the gay community, who even gossiped that the writer was a gay man writing under a pseudonym. Aside from being treasured by gay men, John F. Kennedy also cited Renault as his favourite writer.

Renault was deeply uncomfortable with the idea of someone identifying themselves primarily on the basis of their sexuality.

Renault and Mullard were both involved with the Black Sash movement while living in apartheid South Africa, and although Renault was disappointed at this organisation’s refusal to protest anti-gay laws, calling her a gay rights activist would be inaccurate.

Renault, in fact, was deeply uncomfortable with the idea of someone identifying themselves primarily on the basis of their sexuality. In an afterword to a later edition of The Friendly Ladies, published shortly before her death, Renault expressed her dislike of the Gay Pride movement, writing:

“Congregated homosexuals waving banners are really not conducive to a goodnatured ‘Vive la difference!’ … People who do not consider themselves to be, primarily, human beings amongst their fellow humans, deserve to be discriminated against, and ought not to make a meal of it.”

While these words seem harsh and outdated, it may perhaps be more useful to consider Renault’s contribution to the gay literary canon during a time when writing about queer relationships was very much not the norm: during her career, Mary Renault wrote close to 20 novels and works of non-fiction, most of them featuring queer characters.

Take a look at what scholars, friends and members of the BBC have to say about Mary Renault’s work below.

Leave a Reply